Recent News

PwC joins pioneering Ocean Tech MissionWednesday, November 09, 2016

An Ocean Tech Mission to track “five iconic marine species” in Bermuda to help inform habitat protection at a policy level has been boosted by the news that professional service firm PwC will become a sponsor and mission partner.

Welcome to Callista

Friday, November 04, 2016

Generous donors have joined forces to help buy a new boat for the Bermuda Zoological Society.

Exploring mysteries of the deep

Thursday, November 03, 2016

Scientists often tell us we know more about the surface of the moon than we do about the bottom of our oceans but Bermuda is at the heart of a mission that intends to change that.

Zoological Society Receives New Boat ‘Callista’

Thursday, November 03, 2016

The Bermuda Zoological Society recently purchased a new 30ft Beachcat boat, Callista, thanks to generous donations from Mrs. Diana Bergquist, the Stempel Foundation, Clarien Bank, Somers Isle Shipping and RUBiS.

Turtle project completes 49th year of research

Thursday, October 27, 2016

The Bermuda Turtle Project — a study of seas turtles in Bermuda waters — has completed its 49th year of research.

About

GovernanceAbout Us

Newsletter

Latest News

Gift & Bookstore

Contact

General Inquiries

info@bzs.bm

Latest News

All the latest updates and news from the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum, and Zoo, one of Bermuda's leading visitor attractions!

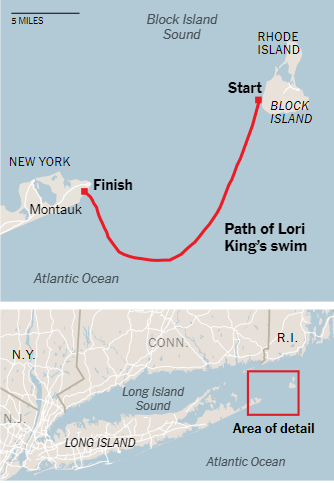

Lori King of Long Island finished a nearly 24-mile trip in 8 hours 39 minutes 45 seconds. Once her swim is certified, King will be recognized as the first person to complete the journey.

Lori King, 47, was swimming toward Long Island when a shark fin suddenly rose from the water.

King was about three-quarters of the way through a marathon swim on Aug. 3 from Block Island, R.I., to Montauk, N.Y. She didn’t see the shark, but her crew saw one of its fins. They knew that the shark could have endangered her and could have threatened her attempt at completing a trek that many had tried but no one had conquered.

Until then, King’s crew had been moving in a sort of diamond formation around her: one boat ahead of King, a kayaker on either side of her, and another boat behind her. Amanda Fenner, who organized King’s swim, said that had the shark gotten too close to King, the crew would have had to pull her from the water a few miles short of finishing the swim of nearly 24 miles.

“I did not want to be the one to make the call,” Fenner said, recalling one of King’s swims in Florida’s Tampa Bay, in 2013, when she was pulled at Mile 21 of a 24-mile swim because a shark started to encircle her. “That crushed her.”

Instead, the boat captains quickly moved out of formation to essentially create a wall between King and the shark. King, meanwhile, did not know about the hiccup until after she finished the swim.

“I knew that something was happening, but I didn’t know what those somethings were,” King said. “I knew I’d hear about them after.”

That shark wasn’t the only issue King and her crew faced on their trip. They also saw two other sharks, jellyfish, dolphins and a baby squid. Some of the crew members vomited with seasickness.

At one point, King suffered such severe cramping that she couldn’t kick with her right foot. And throughout her swim, she was forced to contend with cold surges of water — while wearing only a bathing suit, cap and goggles.

But after 8 hours 39 minutes 45 seconds, King completed her journey, considered a marathon swim for being at least 10 kilometers (6.2 miles). If her trek is certified, as expected, by the Marathon Swimmers Federation, a process that could take several months, she will be acknowledged as the first person to swim from Block Island to Montauk.

“I had to tell myself, ‘You just have to be comfortable with being very uncomfortable,’” said King, who started swimming as a child. “That’s that fine line where it can either make or break whether you’re going to continue or not.”

Mid- to late summer brings out several marathon swimmers across the United States and beyond, stroking through seas, lakes and rivers to take advantage of generally warmer water and calmer currents. The federation has several swims on its docket to verify.

Marcie Honerkamp, who observed King’s swim, said that to avoid strong currents, King could not swim directly in a straight line between Block Island and Montauk. Instead, she had to swim 23.9 miles in a wide U shape bearing south, farther into the Atlantic Ocean. The closest tips of Block Island and Montauk are about 13 miles apart.

“She swam 23 to stay in the current, otherwise I believe it would take her to Connecticut,” Honerkamp said. “It would sweep her out. It would be too strong for her to fight against.”

Janine Serell, another observer of King’s swim for the federation, said that the tides and their timing were part of what made the swim challenging.

“She’s got to be fast enough to get it done before the tides change,” Serell said. “It’s a swim that multiple people have tried before and haven’t been able to get.”

As observers, Serell and Honerkamp kept a log of the swim. They made notes every half-hour of strokes per minute and wind speeds, plus air and water temperatures.

Facts from these logs are later verified during the certification process. Observers also make sure swimmers are unaided, and do not rest by holding on to a boat or by pushing off another object or person.

King has been certified by the federation previously for longer swims. In June, she swam 26 miles in the Kaiwi Channel, from the Hawaiian island of Molokai to the island of Oahu, in 14 hours 38 minutes, according to the federation. In 2016, she swam around Bermuda — covering a distance of 36.5 miles in 21 hours 19 minutes 45 seconds — becoming the first woman to do so.

Her résumé includes dozens of marathon swims. For King, this swim was personal because the waters around Long Island are where she first started open-water swimming with a group.

“No matter what I’ve done during the year, no matter what big swims, I always come back to the group,” King said.

To prepare for the swim, King, who is a public health researcher, spent several weeks training, swimming a base of roughly three miles per day. The longest swim of training, which is about 15 miles, is less about distance and more of a chance for King to see if she can withstand water temperatures, to be in the water for an extended period and to look out for any other possible issues. While King swims freestyle in open water, most of her training is done in a pool, where she practices all types of strokes to mix up her muscle use, heart rate and speed.

“Every swim is a reset for me, and I treat each new swim and training, regardless of distance, as if it is my first,” King said. “I do not think that just because I finished a difficult swim I will automatically slay another one. Each swim keeps me nervous, and, in the end, humble as you realize just how easily it could have gone the other way. ”

Beyond the physical preparations, the logistics of the trip were a challenge of their own that required months of meetings to figure out details, such as water temperatures and moon phases that could affect tides and wildlife in the water.

Along with the observers, King’s escort team included two boat captains, two kayakers and someone to watch the weather.

“Each person that was brought on had one specific job just to make sure it was executed perfectly and there was no distractions,” said Fenner, who took the lead in planning King’s swim.

“We tried to keep as much stressful information away from her, so she doesn’t know about it,” Honerkamp said. “We just kind of said: ‘Keep swimming, keep swimming, keep swimming. We’ll take care of the rest.’ That’s how the whole team worked.”